Balance Your Brain: Amino Acids and the Blood-Brain Barrier

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

The brain is so vital to life that it must be protected and shielded from foreign substances like toxins and pathogens that can cause lethal damage. This protection comes in part from a highly selective membrane called the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB surrounds the brain and is semipermeable, meaning it allows some materials to cross from the blood into the brain but prevents others from gaining access. This is especially important when we consider that brain health is dependent, in large part, on our neurotransmitter levels, which in turn are affected by amino acids. In this article, we’re going to look at the complex interplay between amino acids and the blood-brain barrier and the steps you can take to balance your brain.

All Aboard the BBB Express

The blood vessels and lymphatic vessels of the body are lined with special cells called endothelial cells—the only cells in direct contact with the blood. Between these cells are small spaces that allow substances to pass from the vessels into the bloodstream. This is how, for example, nutrients from the food we eat pass from the gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream.

In the brain, endothelial cells fit very tightly together to prevent a variety of substances from passing into or out of the brain. Water, gases, and some fat-soluble substances can pass through this barrier by passive diffusion—a process by which materials travel down a concentration gradient. However, other substances, such as certain nutrients, are made up of molecules that are too large to pass through the blood-brain barrier easily.

These and other molecules thus require specific transporters. There are transporters for glucose (the preferred fuel source for the brain) and for amino acids that serve as important chemical messengers in the brain. Some amino acids, like glutamate, act directly as neurotransmitters, while others serve as precursors, or “building blocks,” of neurotransmitters that are assembled in the brain.

Whether an amino acid acts as a neurotransmitter on its own or is used to create other brain chemicals, it’s important that concentrations of these building blocks are closely regulated to ensure brain balance, as maintaining appropriate levels of neurotransmitters is vital to well-being and good mental health.

However, there is no unique transporter for each individual amino acid. Rather, there are several transporters, each of which is used by amino acids that share certain chemical properties, such as size or ionic charge. The names of these transporters are hardly what you’d call catchy—for example, system L, EAAT1, ASCT2—and they’re sometimes identified by different designations, so let’s not get caught up in the specifics.

However, it’s helpful to have a basic understanding of why these shared transporters are so important. That’s because the requirement to share transporters makes this a competitive transport system—which means the amino acid that’s present in the largest concentration in the blood has the best chance of getting carried into the brain.

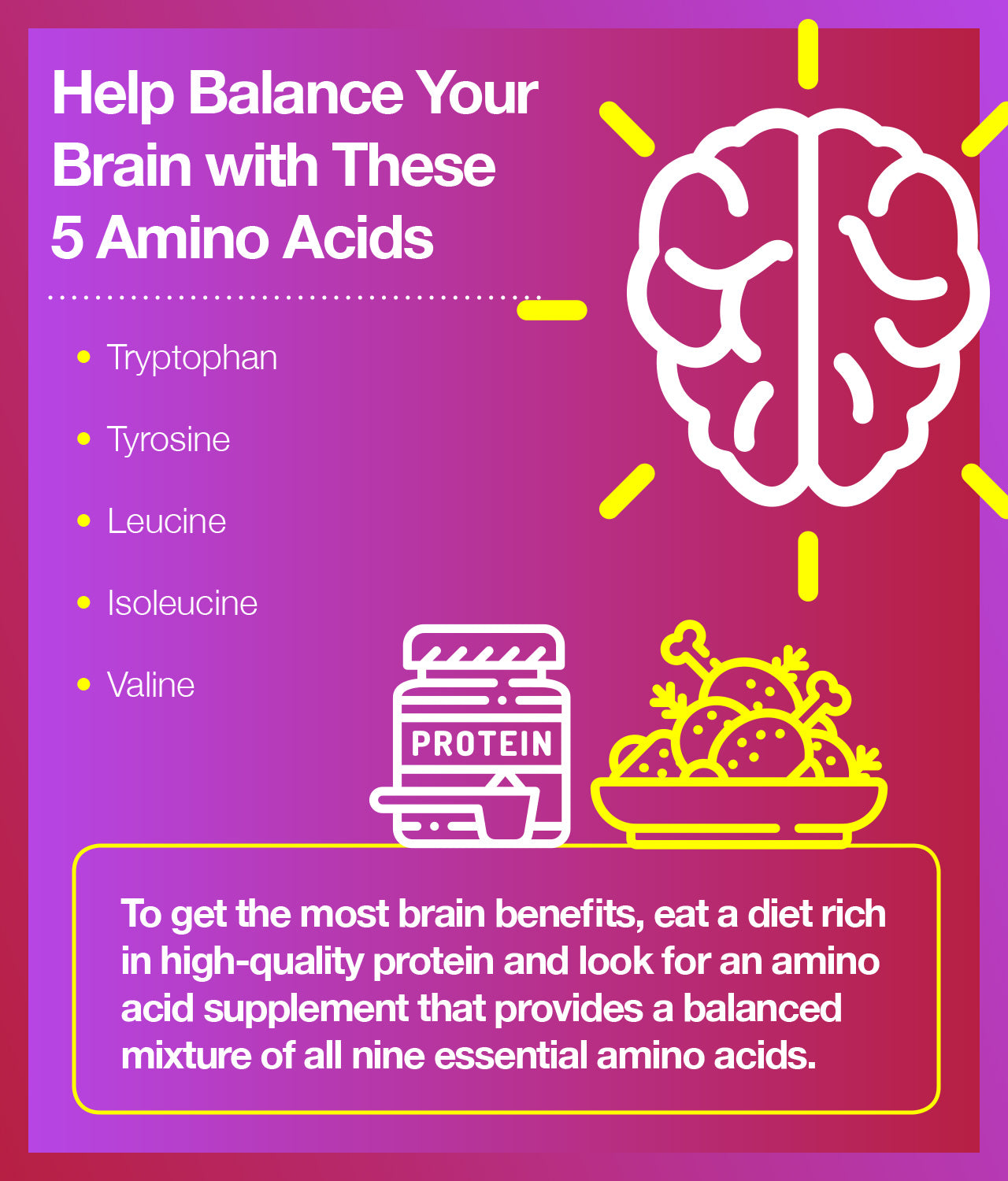

Take, for example, the large neutral amino acids, for which there is one shared transporter. The large neutral amino acids include tryptophan (or L-tryptophan), tyrosine (or L-tyrosine), and the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine.

If blood levels of tryptophan are increased, then a greater amount of this amino acid enters the brain. Once in the brain, tryptophan is converted into the inhibitory neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin is involved in maintaining a positive mood and plays a role in appetite, digestion, sleep, memory, and sexual desire and function.

Low serotonin levels are associated with anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive behavior. In fact, the most widely used family of antidepressants, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), work by blocking reabsorption of serotonin in the brain, thus increasing levels of this important neurotransmitter.

Tyrosine, by contrast, is a precursor of the excitatory neurotransmitter dopamine—another major neurotransmitter that’s central to the brain’s reward pathway. Dopamine helps motivate us to continue certain behaviors, like eating or sex, by triggering feelings of pleasure. Dopamine also plays an important role in movement, learning, memory, focus, and alertness.

Theoretically, if tryptophan is present in high concentrations in the blood, more tryptophan gets into the brain, which yields higher serotonin levels. By contrast, high concentrations of tyrosine decrease tryptophan uptake and increase dopamine levels.

So, as you can see, specific concentrations of amino acids can greatly influence the brain’s neurotransmitter levels, which can have a profound impact on both mood and behavior.

Using Amino Acids to Balance Your Brain

Studies on animals have shown that the production of neurotransmitters in the brain can be manipulated by administering specific amino acids in large enough concentrations to increase brain uptake relative to other amino acids that share the same transporter.

Of course, these types of studies can’t readily be performed in people because it’s difficult to measure exactly what changes occur inside the human brain. Even so, it seems reasonable to infer that the use of amino acids to control brain chemicals may assist us in achieving whatever mood, energy level, or other therapeutic effect we desire.

However, the body is very clever at adapting to drastic changes in its environment, so we need to use a bit of caution when attempting to alter our mood or behavior with amino acids—especially pharmacological doses of single amino acid supplements.

For example, when anabolic steroids like testosterone are misused for bodybuilding, the testicles stop producing endogenous testosterone because the levels in the body are already too high.

Similarly, constant exposure of the brain to high levels of a chemical elicits changes designed to minimize responsiveness and maintain function within the normal range. It’s this phenomenon that explains the tolerance people experience with excessive use of drugs and alcohol.

A more natural way—and a more reasonable approach—to optimize amino acid availability at the blood-brain barrier is to provide a steady complement of all the amino acids. And the best way to do this is to eat a diet rich in high-quality protein and to utilize balanced mixtures of supplemental essential amino acids.

But if you do want to try single amino acid therapy, you should be sure to take the amino acid in the postabsorptive state (several hours after your last meal) to minimize the presence of competing amino acids. In addition, it’s best to follow the manufacturer’s recommended dose and instructions on duration of usage.

Moreover, because no two individuals are alike, each person will vary somewhat in terms of how amino acids affect them and their brain chemistry. This applies not only to the making of brain neurotransmitters but also to how we process and react to them.

It’s also wise to remember that the blood-brain barrier exists to protect the brain—and it’s very good at its job. Likewise, the system of transporting amino acids into the brain is very sophisticated in its ability to regulate the availability of the amino acids used as both precursors of brain chemicals and important neurotransmitters in their own right.

Therefore, ensuring a good supply of all the essential nutrients the brain requires can help prevent neurotransmitter imbalances and provide an excellent foundation for optimal brain function.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: benefits

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620