Proteins vs. Free Amino Acids: Which Is Easiest for Your Body to Digest and Absorb?

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

Protein—and the essential amino acids it contains—serves as one of the most vital fuel sources for the human body. Protein takes on a special importance for anyone engaged in physical activity—and in particular, endurance sports. Research indicates that using protein as a fuel source can significantly increase the time it takes to reach exhaustion as well as reduce post-exercise muscle damage. However, diverting energy to metabolize protein can adversely impact athletic performance and come with unpleasant gastrointestinal effects. This leads many to wonder whether free amino acids might be a preferable fuel alternative.

In order to evaluate the relative merits and disadvantages of free amino acids and dietary proteins, you must understand the composition of both protein and amino acids, as well as how the body processes them after ingestion. In this article, we'll first define relevant terms related to protein and amino acids, then give a brief description of the digestive processes that transform the proteins you eat into the amino acids that will be delivered through the bloodstream to all the tissues and organs in the body, and finally, we’ll cover the speed at which free amino acids can be digested and absorbed compared to the rates of protein digestion.

Understanding the Importance of Amino Acids

In scientific terms, amino acids can be defined as organic compounds containing a basic amino group (-NH2) and carboxyl group(-COOH) in combination with a side chain (R group) that varies depending on the amino acid. Researchers have identified approximately 500 naturally occurring amino acids, 20 of which can be found in the human genetic code.

In the form of proteins, amino acids form the second-largest component of human muscles and other tissues (the first is water). That's why you'll often see amino acids referred to as the building blocks of protein.

Amino acids play crucial roles in protein synthesis, gene expression, and the creation and function of neurotransmitters. For example, two amino acids—glutamate (standard glutamic acid) and gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)—are the primary excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters.

Several amino acids also carry out integral roles as metabolic intermediates. For instance, arginine (sometimes abbreviated to "arg"), citrulline, and ornithine all contribute to the urea cycle, the body's primary mechanism for the removal of nitrogenous waste.

The Basics of Essential, Nonessential, and Conditionally Essential Amino Acids

Experts classify amino acids into numerous amino groups. The 20 amino acids coded into human DNA are known as the proteinogenic amino acids, standard amino acids, or common amino acids. The standard amino acids can be subdivided into three smaller amino groups:

Nine of the standard amino acids have been determined to be "essential" because the human body cannot produce them, meaning it's essential that you take in an adequate supply from the food you eat or from dietary supplements.

The 11 nonessential amino acids unquestionably make significant contributions to your health and well-being. They're just as important as the essential amino acids, but because they can be generated by the human body, they're not categorized as essential.

That said, seven of the nonessential amino acids exist in their own subgroup: the conditionally essential amino acids. While your body can produce these amino acids, under certain conditions, it becomes essential that you augment that supply.

What About Branched-Chain Amino Acids?

If you pay any attention to the world of sports nutrition, you've likely encountered the term branched-chain amino acids (or BCAAs) before. Three essential amino acids, leucine (sometimes shortened to "leu" in scientific articles), isoleucine (or "ile"), and valine, share a characteristic branched structure.

One of the three, leucine, receives the lion's share of the attention in the discussion about branched-chain amino acids—and for good reason. Leucine is the most abundant essential amino acid found in muscle protein, and it also serves as a regulator for protein biosynthesis.

Because metabolism of the three branched-chain amino acids is interconnected, the greatest benefits occur when all three are ingested as part of a balanced amino acid supplement. Studies show that supplementing with branched-chain amino acids can increase lean muscle mass, decrease mental fatigue, and more. It even appears that branched-chain amino acids can delay the progression of liver diseases.

Key Facts About Amino Acid Metabolism

Each of the 20 standard amino acids gets synthesized by a different metabolic pathway. The complexity of that pathway reflects the chemical makeup of the amino acid being formed. The metabolic pathway for the synthesis of an amino acid differs from the pathway by which it is catabolized, or broken down.

Some amino acids are glucogenic, meaning the body converts them into glucose, while others are ketogenic, which means the body converts them into fat.

When you consume dietary protein, the primary site for amino acid metabolism is the liver, though some specific amino acids get broken down in the kidneys or muscle tissue.

Protein molecules, in scientific terms, are polypeptide chains composed of multiple amino acids joined by peptide bonds. The number of amino acids linked together to form the polypeptide chain for a protein varies dramatically from a few dozen at the low end all the way up to the thousands. Within the polypeptide chain, each protein contains different ratios of the 20 standard amino acids.

Eating high-quality proteins is undoubtedly a healthy and effective way to deliver essential amino acids to your body. When we describe a protein source such as meat, fish, eggs, and some dairy products, vegetables, and legumes as high quality, that means it contains a good balance of amino acids with a desirable ratio of essential to nonessential amino acids.

Even the most high-quality protein sources, however, may not be ideal in terms of digestibility, absorbability, and bioavailability, all of which determine whether amino acids will be available when your body needs them most.

An Overview of the Digestive Process

The gastrointestinal tract, or gut, refers to the entire system involved in the digestion of food. It is basically a tube that starts from the mouth, extends down through the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and intestines, and ends at the rectum and anus.

The small intestine has three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. Each section has its own distinct purpose and the selective absorption of various nutrients is divided among the three.

The first part of the small intestine, the duodenum, serves as the the mixing site for many different enzymes from the stomach, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. The duodenum is located between the stomach and the jejunum, the middle part of the small intestine.

The second part of the small intestine, the jejunum, is the primary site for nutrient absorption, as it is lined with enterocytes. These specialized cells are optimized for the absorption of small nutrient particles previously digested by enzymes in the duodenum.

The final and longest segment of the intestine is the ileum, where bile acids and vitamin B12 get absorbed, as well as leftover products of digestion that were not absorbed by the jejunum.

The juncture at the end of the ileum—the terminal ileum—begins the large intestine, which consists of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anus. These structures comprise the last part of the gastrointestinal tract where water is absorbed and the remaining waste material is stored as feces before being removed by defecation from the colon and the rectum.

Breaking Down Dietary Proteins

Like all foods, dietary protein must be digested and broken down to its smallest components in order to be absorbed from the gut and distributed throughout the body.

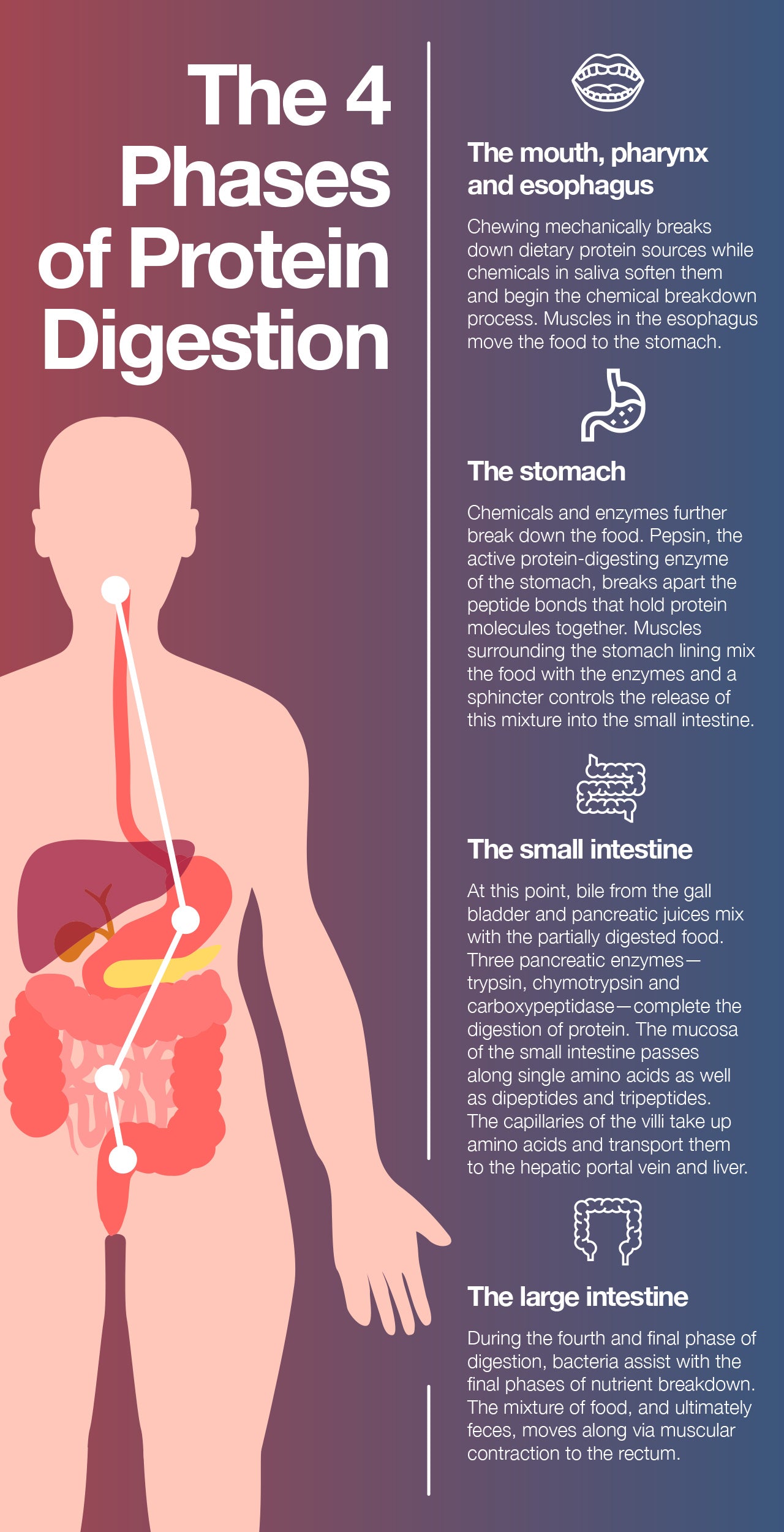

The First Phase: The Mouth, Pharynx, and Esophagus

Our body use numerous processes to break down proteins and access the nutrients they contain. The first step in that process? Chewing, a mechanical means of separating food into smaller, more digestible parts. While we chew, compounds in our saliva soften the food and begin the chemical breakdown of macronutrients.

Next, muscles in the esophagus assist in the process of swallowing food on its way to the stomach.

The Second Phase: The Stomach

Once in the stomach, the food is exposed to more chemicals and enzymes that further break it down to simpler nutrients and nutritional components. This process results in a mixture of partially digested food and water called chyme.

For our purposes, one of the enzymes food encounters in the stomach deserves to be highlighted: pepsin, the active protein-digesting enzyme of the stomach. Pepsin acts on protein molecules by breaking the peptide bonds that hold the molecules together.

Muscles that surround the lining of the stomach help to mix the food in with digestive enzymes, and a specialized sphincter (ring of muscle) controls the rate at which the chyme is introduced to the small intestine. There is also a sphincter at the top of the stomach, called the pyloric valve, that prevents food from going back up into the esophagus.

The Third Phase: The Small Intestine

Bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic juices from the pancreas are introduced to chyme in the duodenum. Digestion of protein is completed in the small intestine by the pancreatic enzymes trypsin, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidase. This mixture is passed onto the jejunum.

The small intestine mucosa can only transport single amino acids or short polymers of two to three amino acids known as dipeptides and tripeptides. Because the inner lining of the small intestine is quite thin, nutrients can readily pass through it into the bloodstream. The wall of this portion of the intestine is made up of folds, each of which has many tiny finger-like projections known as villi on its surface. Furthermore, the epithelial cells that line these villi possess even more microvilli, resulting in an extremely large surface area for the absorption of nutrients from food. The villi contain large numbers of capillaries that take the amino acids and glucose produced by digestion to the hepatic portal vein and the liver.

The Fourth Phase: The Large Intestine

Layers of circular and longitudinal smooth muscle enable chyme to be pushed along the ileum by waves of muscle contractions. Gut motility is the term given to the stretching and contractions of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract, and peristalsis is the term for the synchronized contraction of these muscles.

The semi-solid chyme that reaches the large intestine is comprised of fiber and non-digestible components of food. There are no villi in the large intestine, but there are bacteria that help in the final stages of digestion. Muscular contraction is a very important component of digestion throughout the small and large intestines, as it is necessary to move the chyme (and ultimately feces) through the body towards the rectum.

What Happens to Amino Acids During Protein Digestion?

Your body transports the free amino acid pool created during protein digestion, along with remaining dipeptides and tripeptides, using a process called secondary active transport. Active, in this case, means that the process requires energy, and the difference between primary and secondary active transport is the source of energy.

In primary active transport, energy is derived directly from the breakdown of ATP. The energy that fuels secondary active transport, however, comes from coupling the transport of ions along with the amino acid.

The key moment for amino acid absorption during protein digestion occurs in the jejunum. At this point, any remaining dipeptides and tripeptides are cleaved to form individual amino acids inside the enterocytes, the specialized cells that absorb small nutrient particles. Individual amino acids are then passively transported past the permeable lining of the small intestine and into the bloodstream.

The Pros and Cons of Free Amino Acids and Dietary Proteins

As we've discussed, intact proteins must be broken down to individual amino acids in order to be absorbed from the gut into the bloodstream. Therefore, a primary difference between consuming free amino acids versus dietary proteins relates to matters of digestion.

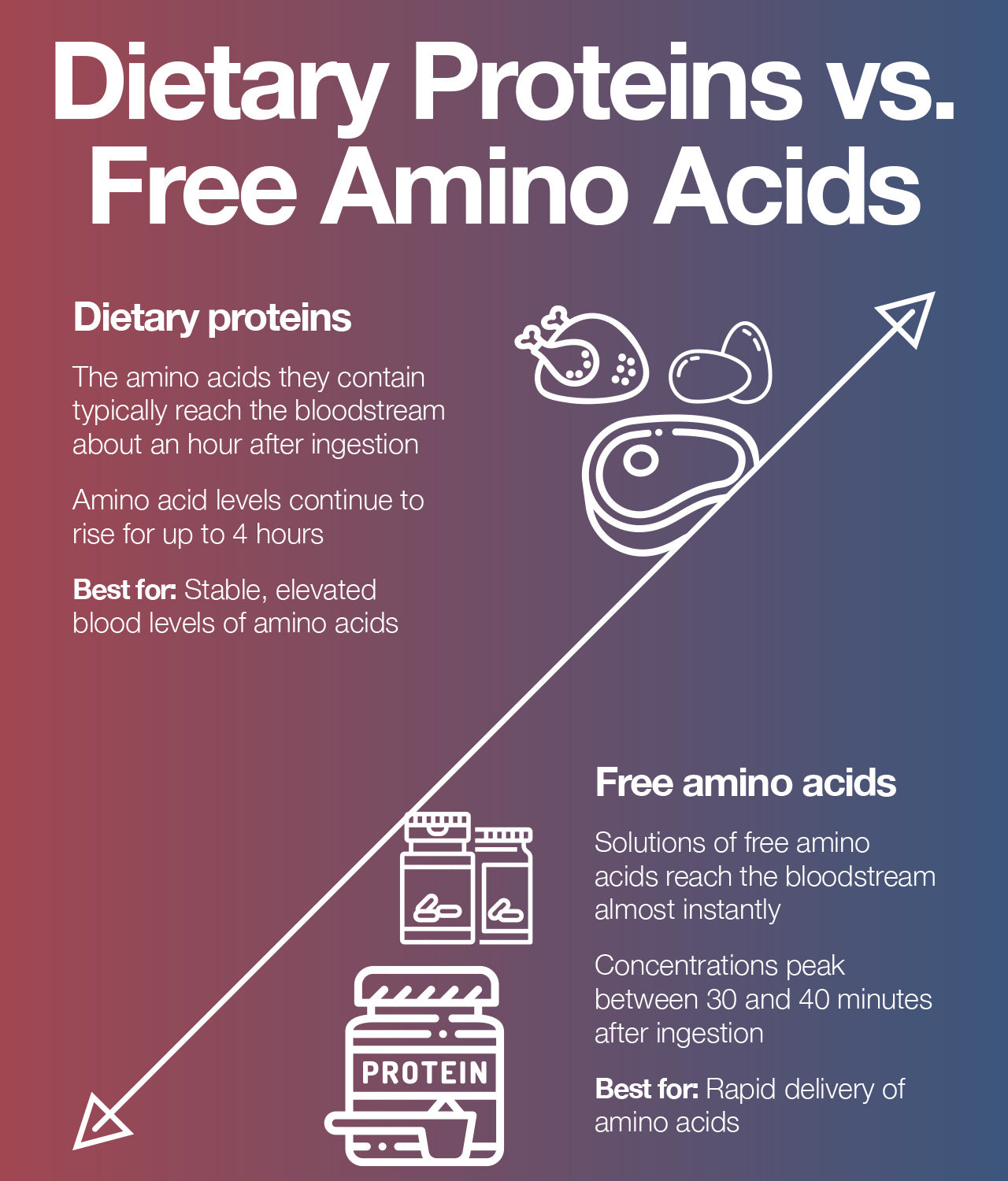

A solution of free amino acids will be absorbed very rapidly and appear in the bloodstream within minutes, reaching peak concentrations between 30 and 40 minutes.

Dietary proteins vary quite a bit in the rate of amino acid delivery because of the other nutrients food contains; for example, fat molecules affect the digestion rate. On average, dietary proteins will release amino acids into the blood within an hour of eating, and amino acid concentrations will continue to rise up to 4 hours after a meal.

Both these patterns of digestion and absorption have their own distinct benefits. The amino acids contained in dietary proteins release more slowly into the bloodstream but result in higher concentrations of amino acids for longer periods of time. Solutions of free amino acids enter the bloodstream almost immediately, but concentrations drop more quickly. Neither is universally preferable.

Therefore, the best approach is to decide on a case-by-case basis whether dietary protein or free amino acids will best meet your needs. And in a long-term sense, you will see the greatest benefits from including both high-quality dietary proteins and balanced mixtures of essential amino acid supplements in your dietary regimen.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: knowledge

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620