Sjogren’s Syndrome: When It’s More Than Just Dry Eyes and Dry Mouth

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

Everyone suffers from the occasional dry mouth or dry eyes. Usually, upping the hydration and using over-the-counter eye drops will clear up symptoms. But if symptoms persist or get worse, there could be an underlying cause, such as Sjogren’s syndrome.

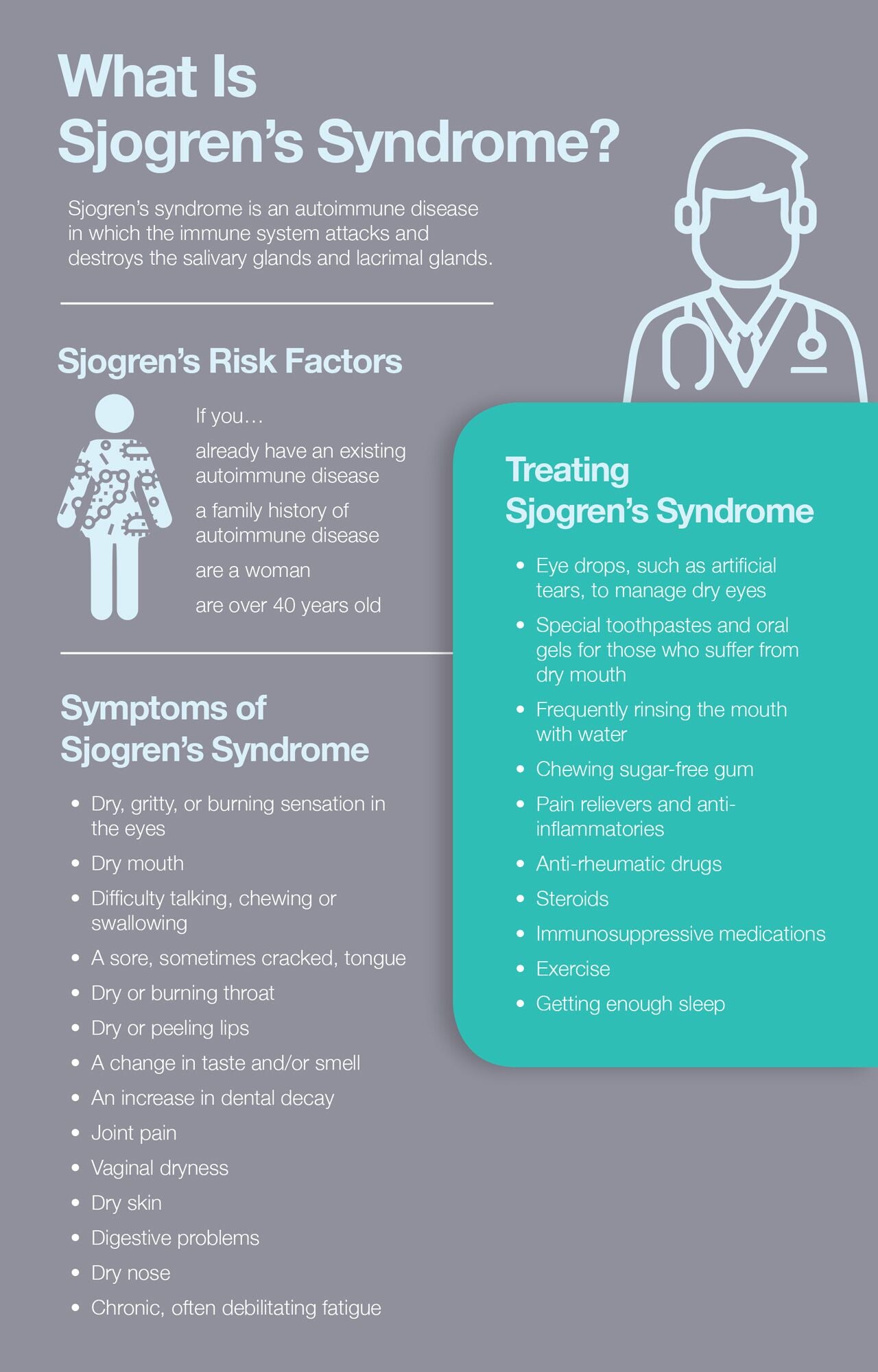

What Is Sjogren’s Syndrome?

Sjogren’s (pronounced Show-grin’s) syndrome is named after Swedish physician Henrik Sjogren. Dr. Sjogren initially became aware of patients suffering from an unknown condition that involved dry eyes, dry mouth, and arthritis in the early 1930s. Intrigued, Dr. Sjogren continued to study patients with these symptoms and ultimately concluded that they were the result of a systemic disease, which is now named after him. Dr. Sjogren continued to research and practice in the fields of ophthalmology and rheumatology into the 1970s.

Sjogren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease, meaning the body’s immune system is misfiring and attacking healthy cells. Autoimmune disorders such as Sjogren's syndrome confuse the immune system, causing it to mistake healthy cells, tissue, joints, and organs for dangerous invaders such as bacteria and viruses.

In the case of Sjogren’s syndrome, the immune system sends white blood cells to attack and destroy the body’s moisture-producing glands. These include the salivary glands, which produce saliva, and the lacrimal glands, which produce tears. While the disease primarily targets these glands, it can progress to targeting other parts of the body including the joints, nerves, blood vessels, and organs like the liver, kidneys, lungs, and thyroid.

Autoimmune diseases are common in the United States. The American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association reports that there are over 100 different autoimmune diseases, and 50 million Americans have been diagnosed with some form of autoimmune disease. Doctors aren’t sure why, but autoimmune disorders are far more prevalent in women than in men, with 75% of cases diagnosed in the U.S. being women. The Sjogren’s Syndrome Foundation reports that over 4 million Americans have been diagnosed with Sjogren’s syndrome, making it one of the most common autoimmune diseases.

Sjogren’s Risk Factors

While no one knows exactly what causes the immune system to begin attacking the body’s moisture-producing glands, certain risk factors have been identified. One may be at a higher risk of developing Sjogren’s if any of the following applies.

- Existing autoimmune disease: Those who already have one autoimmune disease are more likely to develop another. It’s possible the risk increases even more if one already has a rheumatic disease specifically. Sjogren’s is often seen in patients who have systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other connective tissues diseases.

- Family history of autoimmune disease: Doctors have identified a genetic link in autoimmune diseases, and they often do run in families. However, family members will not necessarily have the same autoimmune disease. For example, a parent may have lupus while one child develops Graves’ disease and another child develops rheumatoid arthritis.

- Sex: Women are far more likely to develop Sjogren’s syndrome. The Sjogren’s Syndrome Foundation reports that 9 out of 10 cases of Sjogren’s are in women.

- Age: Sjogren’s can be diagnosed at any age but is typically seen in people over 40.

Symptoms of Sjogren’s Syndrome

The two most common symptoms of Sjogren’s syndrome are dry eyes and dry mouth. However, Sjogren’s is a systemic disease, meaning it can attack and affect the entire body. The Sjogren’s Syndrome Foundation highlights the following Sjogren’s symptoms:

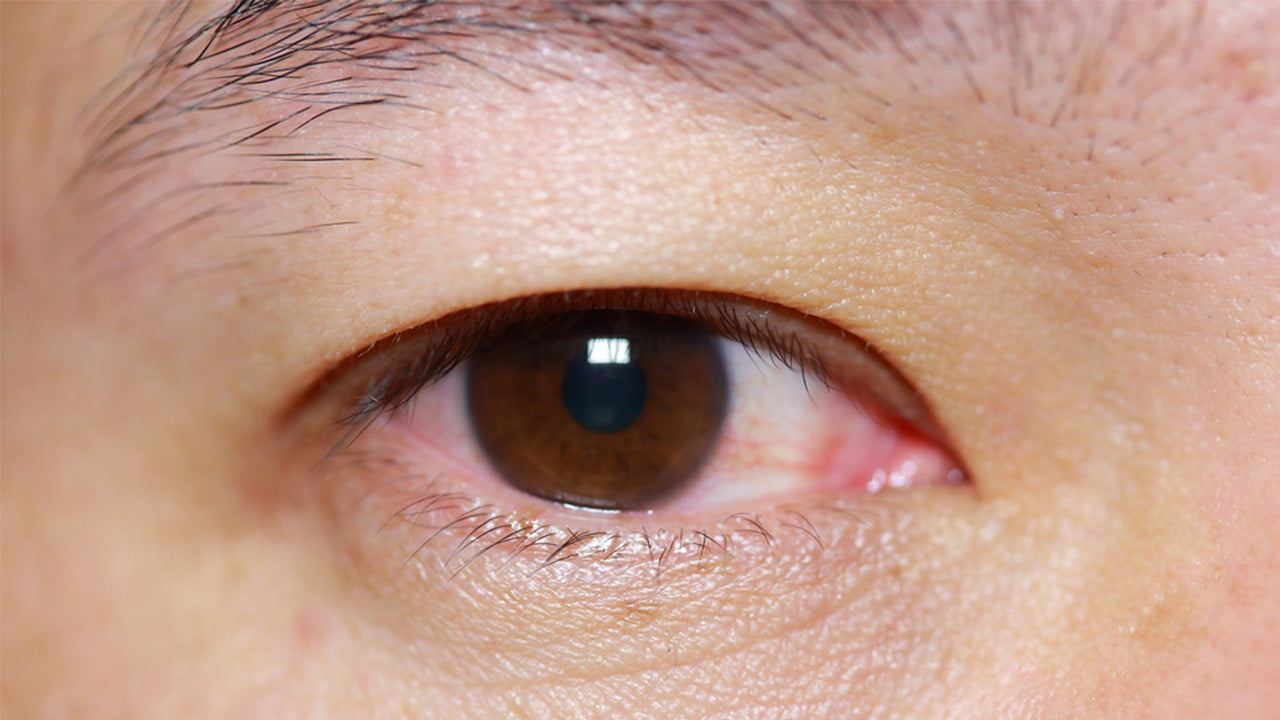

- Dry, gritty, or burning sensation in the eyes

- Dry mouth

- Difficulty talking, chewing, or swallowing

- A sore, sometimes cracked, tongue

- Dry or burning throat

- Dry or peeling lips

- A change in taste and/or smell

- An increase in dental decay

- Joint pain

- Vaginal dryness

- Dry skin

- Digestive problems

- Dry nose

- Chronic, often debilitating fatigue

Types of Sjogren’s Syndrome

Doctors have identified two ways that Sjogren’s may develop. These are:

- Primary Sjogren’s syndrome: Primary Sjogren’s is diagnosed when no other disease is present.

- Secondary Sjogren’s syndrome: Secondary Sjogren’s means that Sjogren’s accompanies another disease, usually an autoimmune disease and often of a rheumatic nature, such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosing Sjogren’s Syndrome

The first step in getting a diagnosis of Sjogren’s is usually ruling out other possibilities, such as certain medications that have been known to cause dry eyes and dry mouth. These include antihistamines, antidepressants, and blood pressure medications. Once a physician has ruled out medications, he or she will perform a series of tests.

As with many autoimmune diseases, there is no single test that can definitively diagnose Sjorgen’s. Sjogren’s also shares many symptoms with other autoimmune diseases, which can make it even more challenging to narrow down the list of possible culprits. Diagnosis typically begins with a series of blood tests. Standard blood tests used to diagnose Sjogren’s include:

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA): An ANA test detects autoantibodies, or antibodies against oneself. If a patient has a positive ANA test, it doesn’t necessarily mean he or she has an autoimmune disease. But it does make an autoimmune disease a possibility.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): An RF test is used to help doctors identify the presence of a rheumatic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or Sjogren’s. Not all Sjogren’s patients will have a positive RF but about 60-70% of patients will. While an RF test can help determine that a rheumatic condition is present, it does not specify which condition, making additional tests necessary for a diagnosis.

- SS-A and SS-B: These are the antibodies that identify Sjogren’s, though they may also be found in lupus patients. A positive SS-A test is found in 70% of Sjogren’s patients, and a positive SS-B is found in 40% of Sjogren’s patients.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): This test measures the amount of inflammation that is present. A high ESR can help doctors identify an inflammatory condition, including Sjogren’s.

- Immunoglobulins (IGs): IGs are normal blood proteins that contribute to the immune system’s response in the body. IGs are typically elevated in Sjogren’s due to the autoimmune response.

In addition to blood tests, doctors may perform physical exams of the eyes and the mouth. Typical exams include:

-

Eye exams:

- Tests to measure tear production, such as the Schirmer test

- Examining the eyes for dry spots

-

Oral exams:

- Tests to measure saliva production during a specified time

- Tests to measure the function of the salivary glands

-

Biopsy:

- A salivary gland biopsy of the lower lip to determine if inflammatory cells are present in the salivary glands

Once all tests deemed necessary by the health care professional have been performed, he or she will use the results as well as the patient’s symptoms, medical history, and family history to make a diagnosis.

Treating Sjogren’s Syndrome

There is currently no cure for Sjogren’s syndrome. Sjogren’s treatment consists of managing the symptoms, which can be done in several ways. Common Sjogren’s treatments include:

- Eye drops, such as artificial tears, to manage dry eyes

- Special toothpastes and oral gels for those who suffer from dry mouth

- Frequently rinsing the mouth with water

- Chewing sugar-free gum

- Pain relievers and anti-inflammatories

- Anti-rheumatic drugs

- Steroids

- Immunosuppressive medications

- Exercise

- Getting enough sleep

Amino Acids

It is possible that amino acids may help with the treatment of Sjogren’s syndrome. Amino acids are often referred to as the building blocks of life. They help the body make protein and chemicals that are essential for a healthy body. A study published in the Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology reported that N-acetylcysteine, a modified form of the amino acid cysteine, improved common symptoms, including eye soreness, eye irritability, and daytime thirst, in Sjogren’s patients.

When it comes to amino acids, it’s best to take a balanced mixture of all essential amino acids to make sure that the blood concentration of amino acids is optimal.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: conditions

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620