The Truth About Complementary Proteins

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

If you’re like a lot of people, you probably grew up hearing that certain foods—especially plant foods—didn’t make a complete meal unless you ate them together. The thinking behind this was that eating a meal that included these complementary proteins was the only way to make sure you were getting enough protein in your diet. But is this really the case? Do we really need to practice protein complementation to ensure we’re eating adequate amounts of protein every day?

Let's explore the answers to these questions and uncover the truth about complementary proteins.

Amino Acids and Protein

All the proteins in the human body are made up of amino acids—the so-called building blocks of life. Although there are more than 300 known amino acids, the body creates all the proteins required for life out of just 20.

Eleven of these 20 amino acids are known as nonessential amino acids because the body can make them on its own. However, the other nine are called essential amino acids because they must be obtained from the foods we eat. These nine essential amino acids are:

- Histidine

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Lysine

- Methionine

- Phenylalanine

- Threonine

- Tryptophan

- Valine

The essential and nonessential amino acids build all the proteins our bodies need by linking together to form long chains, each with a distinct number of amino acids strung together in a specific sequence, depending on the type of protein required.

We must have a steady and balanced supply of all these different amino acids to create the proteins the body must have to carry out its many biological processes—from building muscle to manufacturing brain neurotransmitters.

If even one of these building blocks is missing, protein synthesis doesn’t occur, and protein isn’t created.

Complementary Proteins: Fact or Fiction?

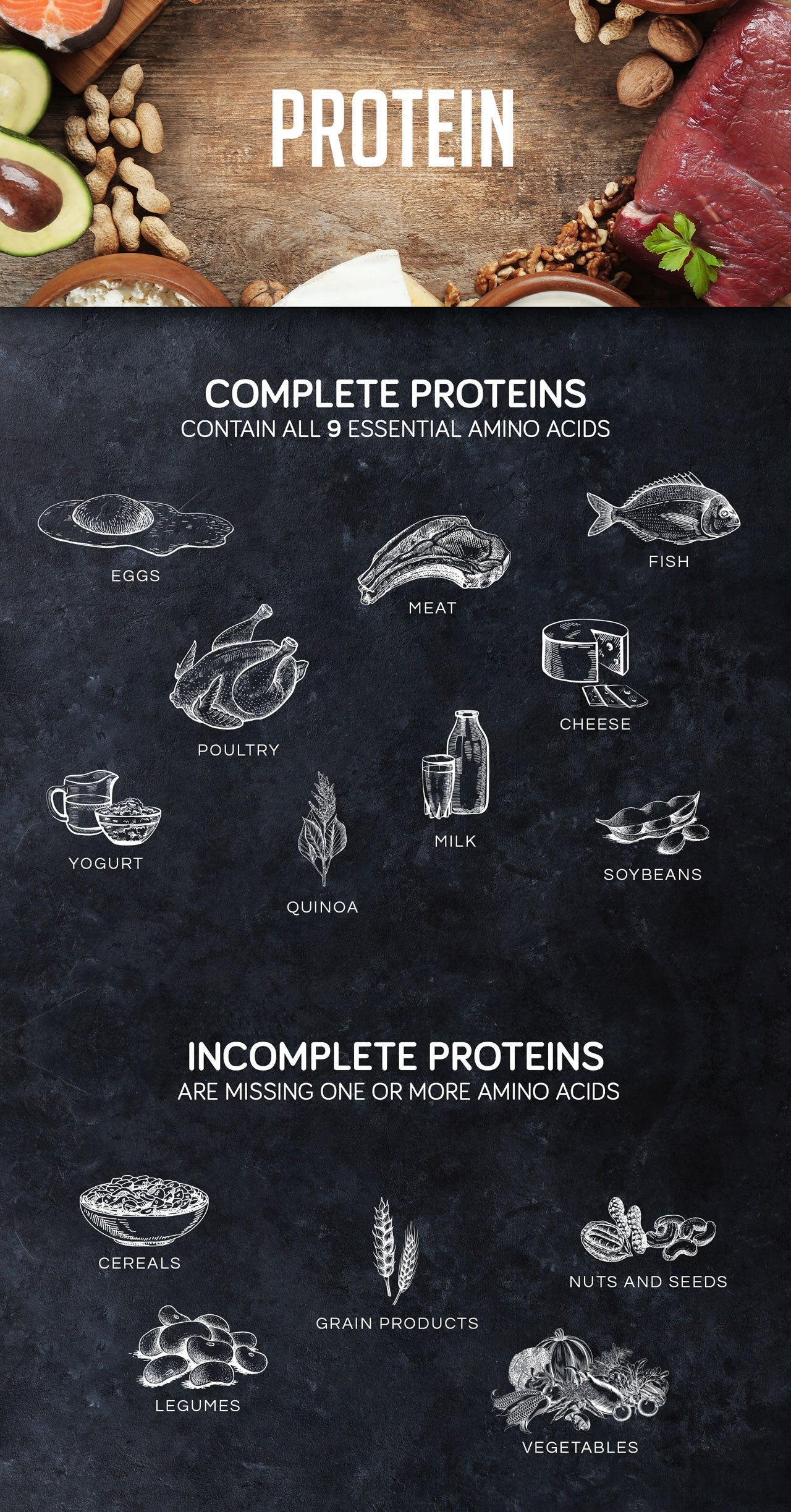

When it comes to protein sources, some are considered complete because they contain all nine essential amino acids, while others are considered incomplete because they’re either missing or have low levels of one or more of the essential amino acids.

For example, foods that come from animal sources—think meat, fish, eggs, dairy products—are considered complete because they contain relatively high levels of all nine essential amino acids.

Contrast this with plant foods, many of which are considered incomplete protein sources because they’re either low in or missing one or more of the essential amino acids.

However, the theory goes that if you combine two incomplete proteins, you end up with a complete protein that contains all the amino acids the body needs to ensure sufficient protein intake.

But is this fact or fiction?

Even a cursory search online reveals quite a few examples of menu options based on the theory of complementary proteins. Some common ones are:

- Lentil soup with whole grains

- Stir fry with nuts and whole grain noodles

- Bean burritos with whole grain tortillas

- Beans and rice

- Hummus (chickpeas or black beans) with whole grain pita bread

- Peanut butter sandwich made with whole grain bread

In looking at this list, we’re sure you noticed the one thing they all have in common: combinations of different plant-based foods.

But according to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the entire thought process behind the theory of complementary proteins is actually quite flawed, as studies have shown that an optimal amino acid profile is perfectly obtainable by eating a variety of protein sources over the course of a day.

If you eat limited, or no, animal sources of protein, you may feel off the hook reading that bit of information.

However, anyone who eats a diet that relies heavily—or completely—on plant-based protein foods needs to keep one important caveat in mind: protein quality.

Take beans and rice—the quintessential pairing that’s often held out as the poster child for complementary proteins.

Although neither beans nor rice is a high-quality protein food source (meaning they both contain limited amounts of essential amino acids, and the ones that are present aren’t as easily digested or absorbed as animal sources of protein due to the added fiber content), when eaten together, they’re said to provide a balanced mixture of all the essential amino acids.

At least in theory.

For while beans are deficient in methionine and grains are generally relatively high in this amino acid, thus offering us a textbook example of complementary proteins, the combination of beans and rice does not a high-quality protein make—especially when you throw the added fiber content into the mix.

The Incomplete Nature of Complementary Proteins

Building on our beans and rice example, let’s now take a look at the peanut butter sandwich made with whole grain bread.

Like beans and rice, a peanut butter sandwich made with whole grain bread technically provides a complete mixture of all the essential amino acids because the combination of peanut and grain protein fills in the amino acid gaps that otherwise occur if either of these foods is eaten alone.

However, the quality of peanut protein is low, and the quality of grain protein is even lower. Moreover, a peanut butter sandwich made with whole grain bread has low protein density—which means there are fewer protein calories than non-protein calories.

What does this mean for you?

It means that the amount of calories you’d need to consume to get enough peanut butter and whole grain bread to meet all of the body’s essential amino acid requirements would exceed your total caloric requirement for the day.

So, although peanut and grain proteins are, in the strictest sense, complementary, a peanut butter sandwich made with whole grain bread is still a very low-quality protein food source.

In addition, to be considered truly complementary, proteins must have complementary profiles of essential amino acids. Unfortunately, the quality of most plant sources of protein is limited by the availability of the amino acid lysine.

Therefore, you’re unlikely to consume two plant proteins that truly complement one another (though some plant sources of protein, including tofu and quinoa, do contain all the essential amino acids).

And this can become a real challenge for vegan diets—and for vegetarian diets that don’t include dairy products.

However, in contrast to the difficulty of finding complementary plant-based proteins that blend to create a high-quality protein source, a typical omnivore diet that combines both animal protein and plant protein foods can be quite effective.

The reason for this is that while most plant-based proteins are limited by lysine, animal proteins contain abundant levels of this amino acid and are therefore perfectly suited to improving the quality of plant sources of protein.

For vegetarians—and especially vegans—who don’t wish to put a variety of animal proteins on the menu, a practical alternative is incorporating a balanced essential amino acid supplement like Life into the diet to address any imbalances in the amino acid profiles of dietary protein sources.

Such a move can greatly improve the ratio of dietary essential amino acids to nonessential amino acids—without contributing much to total caloric intake. And you won’t need to put as much thought into matching the “right” protein foods to make high-quality complementary proteins.

Furthermore, since an essential amino acid supplement has no non-protein components, its protein density is considered complete. And this can be highly beneficial for anyone lacking sufficient variety in their diet—or, for that matter, anyone interested in simply obtaining the many benefits of optimal amino acid nutrition.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: food

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620