Evidence Shows Using Amino Acids for Surgery Recovery Leads to Improved Outcomes

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

Surgery can be a life-saving necessity, but it places significant strain on the human body. Developing a proactive plan for navigating the post-surgery healing process can help surgical patients avoid—or at least mitigate the effects of—pitfalls such as protein-energy malnutrition, the loss of lean body mass, and systemic inflammation. High-quality scientific research indicates that essential amino acids can offset the physical stress caused by surgery and accelerate the recovery process. To understand the benefits of amino acids for surgery recovery, you must first have an understanding of the role amino acids play in the body.

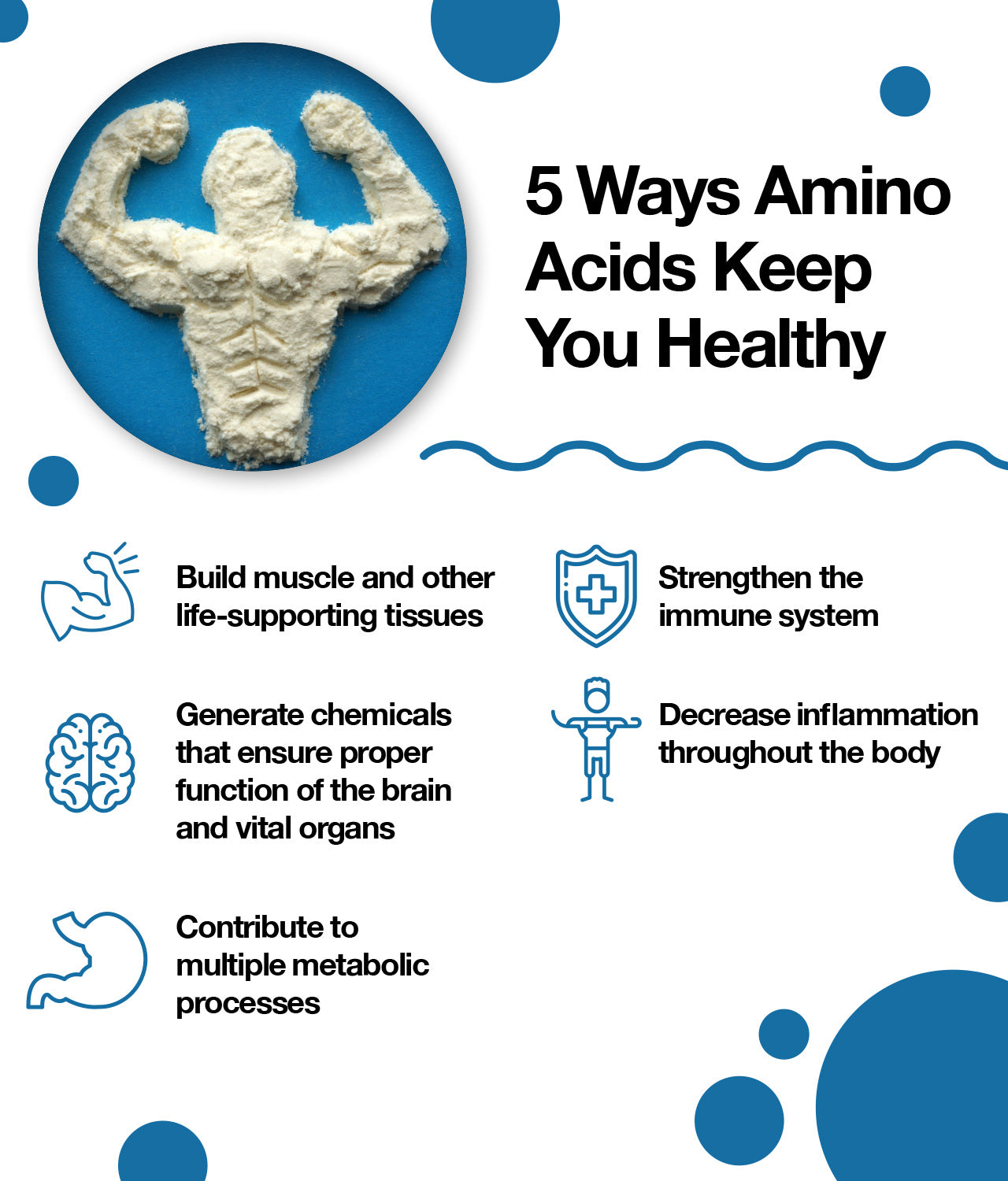

It's no secret that amino acids make vital contributions to your overall health and well-being, particularly when it comes to the growth and repair of muscle tissue.

There are two general types of amino acids: essential amino acids and nonessential amino acids. Both are necessary, but because your body can produce nonessential amino acids, you do not need to monitor your intake in the same way you must do for essential amino acids that must be obtained either from the food you eat or from supplements.

Researchers have found that a subgroup of essential amino acids called branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) increase the body's ability to synthesize protein, regulate the rate of muscle tissue breakdown, repair muscle tissue, and transport fuel into muscle cells.

The Toll Surgery Takes on the Body

Think of surgery as a controlled injury. If you are hurt in a car crash, for example, you can go from perfectly healthy to seriously injured in a matter of seconds. The same is often true in the case of surgery.

When going in for elective surgery, you typically feel fine as the anesthesia is administered, but when you wake up, you feel roughly as if a truck ran over you. And even if an underlying pathological condition necessitates surgery, the stress of the surgery itself increases the challenge of rehabilitation.

Although the exact nature of the stress on the body may differ, the body's response to either the controlled injury of surgery or an uncontrolled injury involves the same fundamental elements. The path to recovery can be nearly identical whether you are healing from an injury or from surgery.

Why People Lose Muscle Mass and Function During Recovery

Whether you are severely injured or recuperating from surgery, one thing’s for sure—you are going to lose muscle mass and function. It’s inevitable. Recovery requires some degree of inactivity, and inactivity means the muscles aren’t maximizing their movement and performance capabilities. This makes a decline in muscle mass and function inescapable. What you can control, however, is the degree of decline. It does not have to be substantial (more on that in a moment).

The detrimental effects of inactivity on muscle mass and function are well established. If you’ve ever had a broken limb put in a cast, you’ve seen the effects firsthand. When it’s time to remove the cast, you’re greeted with the startling withered look of a limb unused. Even if you have been working out the rest of your body, the limb that has remained inactive will show visible signs of decline. An event such as heart surgery that physically limits activity has the same effect as casting a broken limb but on the whole-body level.

The muscle loss triggered by inactivity is amplified by your body’s overall physiological response to injury, which we call the catabolic state. A catabolic state occurs in response to severe injury or illness and is characterized by whole-body protein loss, mainly due to increased breakdown of muscle proteins. The catabolic state can last anywhere from a week to several months.

Anyone who is interested in muscle building for functional or aesthetic reasons knows that failure to consume an adequate supply of nutrients—in particular, protein—slows the body's rate of muscle protein synthesis, resulting in the loss of a certain amount of muscle. When your body enters the catabolic state, the loss of muscle mass and strength occurs at a much faster rate than it occurs in the absence of key nutrients.

The Physiological Processes Behind Muscle Loss

The simplest way to encapsulate the processes that result in muscle loss is to state that when the rate of muscle protein breakdown exceeds the rate of muscle protein synthesis, we lose muscle mass. Our bodies just can’t make enough new muscle protein to offset the rapid rate of muscle breakdown.

When our bodies enter a catabolic state, the rate of muscle protein breakdown shoots way up. It is not unusual for the rate of protein breakdown to increase by more than threefold!

A large increase in the rate of protein breakdown releases a flood of amino acids into the muscle cells. This increased availability of amino acids stimulates the rate of muscle protein synthesis. Unfortunately, the increased synthesis is not enough to balance the increase in breakdown. The net result is a large increase in the loss of muscle protein.

How Hormones and Inflammation Drive the Catabolic State

The catabolic state following surgery, injury, or illness stems from a variety of underlying factors.

First, a flood of stress hormones, most prominently epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol, activate the sympathetic nervous system. You have likely heard this referred to as the fight-or-flight response.

Next, inflammation kicks in. There are two types of inflammation, and their impact on the body is quite distinct. Local, acute inflammation arises at the site of injury or surgery. This type of inflammation can be quite beneficial in the early phase of wound healing. When local inflammation lingers too long, however, it can begin to inhibit tissue repair.

Systemic inflammation, also called long-term, chronic inflammation, has no identifiable benefits. In fact, this type of inflammation can escalate the catabolic state in the whole body, increasing the severity of associated muscle loss.

To better understand the impact systemic inflammation can have on the body, let’s examine that process in the context of a severe burn injury to the leg. A local response at the site of tissue injury would result in a decline in muscle protein synthesis and a loss of muscle mass and strength to the injured leg. A systemic response, however, disrupts muscle protein metabolism in the unburned leg to nearly the same extent as it does in the leg that sustained the severe burn injury.

Furthermore, the consequences of a catabolic state extend beyond muscle loss. Your appetite decreases, making it more difficult to consume the nutrients required to fuel muscle protein synthesis. Metabolic changes transpire, too, such as reduced sensitivity to the action of the hormone insulin. Insulin resistance may persist for months after other symptoms of the catabolic state have resolved.

Using Amino Acid Therapy to Help Your Body Heal

Loss of muscle mass and strength after injury or surgery delays recovery and an individual's return to normal activity. In severe cases, or in elderly individuals with little reserve, muscle loss can be a direct contributor to mortality.

In all cases of injury and surgery, the speed and extent of recovery to normal functional capacity is determined in large part by how much muscle has been lost. Injury or surgery causes muscle loss at a rate so fast that consequences can be evident in a matter of days. If you can decrease the amount of muscle you lose, you can accelerate the time it takes you to recover. A balanced essential amino acid supplement can help tremendously with both those goals.

How Essential Amino Acids Decrease Muscle Loss

In order to decrease muscle mass losses during the recovery period, you must counteract the changes to your body's protein metabolism processes.

After an injury (including the controlled injury of surgery), an alteration in muscle protein metabolism transpires, limiting the normal stimulatory effect of dietary protein on muscle protein synthesis. The lack of responsiveness of muscle protein synthesis to the normal stimulatory effect of dietary protein is called severe anabolic resistance.

The Crucial Role Played by mTOR

Anabolic resistance in the catabolic state occurs because of a molecular factor called mTOR inside the muscle cell. Under normal conditions, mTOR activates muscle protein synthesis, however, anabolic resistance in the catabolic state decreases mTOR activity. In order for muscle protein synthesis to return to optimal levels, mTOR activity must be escalated. Once this occurs, other intracellular molecules involved in initiating protein synthesis respond by escalating their activity levels as well.

So, how do we get mTOR up and running? By supplementing with a complete blend of free essential amino acids formulated with a relatively high proportion of leucine.

Perhaps you're wondering: why not get leucine from the diet? One of the biggest therapeutic challenges presented by the catabolic state that arises after surgical procedures, injuries, or severe illnesses is reduced appetite. Loss of appetite makes it difficult to take in the dietary protein needed to offset increased muscle protein breakdown and help prevent muscle decline. For many, taking a well-formulated amino acid supplement is a desirable alternative to attempting to eat a sufficient amount of leucine-rich dietary protein.

Then there’s the fact that free leucine activates mTOR more efficiently than leucine contained in intact protein. This is because free leucine does not require digestion and is therefore absorbed more rapidly. Free leucine reaches a higher peak concentration in blood more rapidly than when leucine is consumed as part of an intact dietary protein that must be digested before the constituent amino acids can be absorbed. During the catabolic state, therefore, consuming a mixture of free essential amino acids with abundant leucine slows the net loss of muscle protein more effectively than either intact protein in a meal or meal replacement beverages do.

Once mTOR is activated by leucine, an increased availability of a full balance of all the essential amino acids is necessary to stimulate protein synthesis. Single amino acid therapy with leucine, or a combination of the three BCAAs, just won’t do it. Thus, although leucine is the key to overcoming anabolic resistance, consumption of leucine alone is not sufficient to stimulate muscle protein synthesis.

In addition to providing precursors for making new muscle protein, if enough essential amino acids are consumed, concentrations will rise high enough to inhibit muscle protein breakdown and stimulate protein synthesis.

In this way, essential amino acid nutritional therapy during the recovery period following surgery can help you return to full function by protecting against muscle loss. Taking an essential amino acid supplement can:

- Activate mTOR

- Provide amino acid precursors needed to make new muscle

- Inhibit the breakdown of muscle

- Improve the net balance between muscle protein synthesis and breakdown

A stimulation of muscle protein synthesis and inhibition of muscle protein breakdown is the metabolic basis for restoring muscle mass and strength.

Key Scientific Evidence on Using Amino Acids for Surgery Recovery

Much of the work done on how best to preserve lean body mass in the wake of major surgery has been focused on protein breakdown and amino acid oxidation. The manipulation of hormones involved in the development of the catabolic state, as well as the stimulation of insulin and insulin-growth factors, has also been a major priority.

Decreasing the release of so-called catabolic hormones as well as insulin resistance in post-surgery patients has been shown to both lower rates of whole body protein breakdown as well as to minimize decreases to muscle protein synthesis. A key element of this, researchers have found, is providing the correct balance of nutrients.

According to findings published in Anesthesiology, delivering an infusion of amino acids to patients can actually reverse the catabolic state. Previous studies demonstrated that amino acid infusions can decrease whole body protein breakdown and increase protein synthesis, resulting in a positive protein balance.

A research team led by scientists from the Department of Anesthesia at the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal enrolled patients scheduled to undergo colon resection, a surgical procedure that involves a hospital stay. On the second postoperative day, all patients received a solution of 10% amino acids. Levels of whole body leucine and glucose were measured, and blood samples were taken to analyze levels of hormones including cortisol, glucagon, and insulin.

The scientists found that the infusion of amino acids resulted in a positive protein balance as well as other beneficial metabolic effects. Their findings showed that the amino acids suppressed protein breakdown by over 25%, and that 12-16% of amino acids made available from proteolysis were redirected toward protein synthesis. "The infusion of amino acids in the current study caused an average increase in protein balance of 36.7 μmol · kg−1· h−1," the authors wrote. They concluded that even the short-term use of amino acids after surgery can inhibit protein breakdown while stimulating protein synthesis.

A separate study carried out by a team based in Oregon and published in the June 28, 2018 issue of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery focused specifically on how amino acids impact post-surgical muscle volume loss.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial enrolled adult patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA), also known as total knee replacement surgery. The authors' goal was to determine whether supplementing with amino acids during the perioperative period—which includes time spent in the hospital prior to as well as after surgery—can mitigate muscle atrophy.

Study participants ingested either 20 grams of essential amino acids (EAAs) or a placebo twice daily for 7 days prior to their procedures and for 6 weeks following them. Magnetic resonance imaging was used to measure quadricep and hamstring muscle volume at the time of enrollment and at the study's conclusion. Data on functional mobility and strength came from patient-reported outcomes.

Compared with the placebo group, participants who took EAAs experienced significantly smaller losses of mean quadriceps muscle volume in the leg on which the operation was performed as well as their other leg. A greater muscle-volume-sparing effect was seen for the hamstrings of individuals who took EAAs than for those in the control group as well. The authors concluded that EAA supplementation is a safe way to reduce the loss of muscle volume for patients undergoing TKA.

Strategies for Preserving Muscle Strength and Function During Recovery

Even if you're able to use amino acids to alleviate or avoid the the short-term catabolic state that follows physical trauma, your body will enter a depleted state marked by significant muscle loss. This will be evident in overall body weight loss—how many times have you heard that the only good thing about someone’s injury or surgery was that they lost weight?

As recovery continues, the lost weight will be gradually regained. However, without diligent adherence to an exercise and nutrition program, the lost muscle weight will be regained as fat. To return to your daily activities in the best possible health, it is crucial to replace the lost weight with new muscle, not fat. In this article, I go deeper into how amino acids can fuel good weight after a serious illness, injury, or surgery.

For our purposes here, I'll provide an overview of best practices related to exercise and nutritional strategies to rebuild muscle during recovery.

Be Sure to Prioritize Exercise

At the outset of recovery, your capacity for exercise will be limited. Even so, it is essential to engage in both aerobic and resistance exercise as soon as possible.

Depending on the specifics of your situation, it may be advisable—or even mandatory—for you to engage in a structured physical therapy program. Whether or not that is the case, at some point in your functional recovery process, it will be vital to devise your own approach to reintroducing physical activity.

Aerobic exercise can take any form—walking, elliptical, cycling, swimming, and so on—as long as the option you choose elevates your heart rate to 120 beats per minute or above. As you regain your fitness, your speed and the amount of distance you cover will increase.

Some moderate stretching may also be needed to regain range of motion. As strength returns, work up to the recommended guideline of 150 minutes a week of aerobic exercise. However, because most of your cardio output recovery will be walking as opposed to more strenuous aerobic activity, it’s advisable to increase to 5 hours per week of aerobic exercise in addition to resistance sessions.

Resistance exercise is the most important type of exercise for rebuilding muscle. Machines are optimal for resistance workouts, particularly at the outset. The loss of muscle function in the catabolic state impairs coordination, and the possibility of injury is greater with free weights. Machines provide specificity in terms of the muscles involved in any exercise, and this may be of particular importance when addressing specific areas affected by injury or surgery.

The weight lifted should be progressively increased as strength returns. Most individuals will find that they regain lost strength in a shorter period of time than that required to originally gain that strength. The amount of resistance used should be adjusted accordingly. A general guideline is to increase the resistance by 10% per week, but progress may be more rapid in the first few weeks of recovery.

Make a Post-Surgery Nutrition Plan

Nutrition plays a crucial role in recovery. Eating a balanced diet featuring ample high-quality protein is essential. However, that alone will not ensure you regain more muscle than fat.

The single most important aspect of nutritional therapy during the recovery period will be essential amino acid supplementation.

Essential amino acids are the active components of dietary proteins. Balanced essential amino acid supplements stimulate muscle protein synthesis to a greater extent than any naturally occurring protein food source.

Essential amino acid supplements work synergistically with exercise to provide a greater stimulus than either produces on its own. To maximize the beneficial effects of each element, you should take essential amino acids 30 minutes before an exercise session as well as immediately following the session.

When consuming essential amino acids without accompanying physical activity, the greatest effect will be when taken between meals. That said, there is no wrong time to take an essential amino acid supplement. If you miss the optimal dosing window, simply take your EAA supplement at your earliest opportunity.

For more information on a balanced amino acid supplement created for recovery after injury or surgery, check out our Amino Company blends.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: surgery

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620